Life after Surgery: Byers W. Shaw Jr., MD, FACS

Ed Nelson invited me to write something for his “Life After Surgery” Column.

“Which surgery?” I asked.

My dad, a general surgeon in rural Ohio, sutured a half dozen lacerations on my face. I got the first one when I drove my Hollywood Deluxe Stroller (Fig 1a) off the front porch and down a flight of wooden stairs. I landed forehead-first (Fig 1b) on the sidewalk. Dad claimed I tore the closure open by running the demonic stroller through the screen door a week later. The scar became more noticeable as I aged until I had so many wrinkles from squinting against the sun that it disappeared.

Other gashes on my face needed surgery but I’m starting to think that’s not what Ed meant when he came up with “Life After Surgery.”

Twenty years into my career as a transplant surgeon I found a lump in my groin. I was taking a shower in a motel northwest of Torrey, Utah on State Highway 24. I was there with my 14-year-old son Joe to attend the wedding of Dirk Noyes’ middle son, Gavin, to Steph. Joe and I left soon after the last “I do” to go camping in the Waterpocket Fold. That first night in a tent I couldn’t stop fingering the lump. It was big and hard, and I started thinking of death from cancer and how I’d better not risk our youngest child falling to his death out in those hoodoos and waves of sandstone. Imagine spending my last days unforgiven and cancer ridden.

We left after only one day. I’m sure Joe wanted a rational explanation, but I didn’t have one and it wouldn’t have been like me to explain that we had to get home because I’m dying of cancer, then show him the lump as proof.

I had Stage Ⅰ diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and received four cycles of R-CHOP and four of local radiation between summer 2002 and the second day of 2003 (Figure 2). Re-staging at six months showed I was cancer-free and I thought I should probably go back to work. But I knew that meant lots of late-night surgery and I couldn’t get over the not-so-neurotic notion that I got lymphoma in the first place from practicing Professional-Grade Sleep Deprivation since my earliest college days. My partners agreed to let me concentrate on liver and bile duct surgery and for a while it was both satisfying and sleep-tolerant.

I always assumed recovering from cancer would be life-changing, at least in some important emotional way. Instead, I simply felt guilty for not appreciating how lucky I’d been. I guess it was all too easy, the treatment and recovery. Seminal change came later, and it started with mental illness.

On January 15, 2006 I was sitting at my desk sorting slides for a presentation I’d be making the following week. In the adjacent living room, the Steelers, my favorite team, were winning their AFC playoff game against the Indianapolis Colts (they went on to win the Superbowl that year). The weather in Omaha that Winter Sunday was balmy, with a forecast high of 60℉. I planned to take advantage of the unusual weather with a 40-mile bike ride after the game.

Out of the blue, I felt something was wrong with me. I became anxious, which didn’t make sense what with the game going well and our weather so perfect. The anxiety grew until I had to turn off the game, abandon the slides, and go outside to the sun. I thought starting my ride early would help, but after five miles of rising fear, I turned back for home, darkened our bedroom and hid under the blankets. I slept for four hours and woke up feeling fine. Problem over.

A few days later, it happened again in my office: no warning, no apparent reason, just rising terror, a sense of dread and despair. I stood to see if walking the halls might help but my legs felt terribly week and I was suddenly freezing cold. I pulled down the blinds, told my assistant I was feeling ill, lay down on the couch and covered up with my winter coat. I slept for several hours and once more awakened feeling OK. Over the following weeks the attacks increased in frequency. I was afraid to tell anyone. I thought it would just go away, like a cold or a flu, and I’d go back to normal. I eventually got help, and a diagnosis, and started taking pills that helped but didn’t eliminate the problem. I learned to recognize the early symptoms and take a little pink pill that lessened the severity of an attack, but that meant I couldn’t do surgery or patient care, so I’d ask a colleague to stand in for me. I just didn’t feel good, I said. Several years would pass before I got on a regimen that controlled my symptoms and eliminated the acute attacks. More time was required to deal with the shame I felt, especially when I asked my colleagues to allow me to just do elective liver and bile duct surgery — no more late-night transplants. Within a year I would quit surgery altogether. It felt like a shameful thing to do. I wanted so much to share my reasons with my close colleagues, but it felt like a betrayal of them and a terrible failure on my part. I told myself I would rejoin the team as soon as I could be a fully capable member of the team instead of a burden. That never happened.

In the summer of 2007, I was accepted to the Fiction Writing section of the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop[i] at my alma mater. I’d wanted to be a published writer since second grade. My mom encouraged me to write stories the moment I could scribble a full sentence, and she praised every silly tale as though I’d just won a Pulitzer. I went to Kenyon College (Figure 3) in part because my Dad had, but also because it had a great tradition of writing with the likes of E.L. Doctorow, Robert Lowell, and John Crowe Ransom a few of its important alumni and faculty. I majored in Chemistry just to be safe but took every literature course I could.

I graduated Kenyon in 1972, chose the sanctuary of a career in Medicine and soon discovered just how insidiously medical school tried to steal my soul. Desperate to escape, I started submitting works of fiction to various magazines (Redbook, Playboy, Reader’s Digest) that paid for things they published. It was awful stuff, and most of the time I didn’t receive a reply. I had to be satisfied that every now and then someone would send a manuscript back with a polite rejection with words of encouragement to keep trying.

I kept writing stories, however, and at Kenyon in 2007, I discovered that some really good writers are really good critics. They happily told me what they thought worked, and more importantly, what didn’t — priceless gifts, as I would later understand.

In the summer of 2008, I made several decisions, not all of which seemed rational, even to close friends and family. I quit my chairmanship, separated from my wife a week before our 25th anniversary, obtained financial support from the hospital, the practice group, and the university to create point-of-care patient management software, and finally committed fully to a life without the operating room. My interest in making computers streamline clinical workload and collecting data for clinical research dated back to my years in Pittsburgh. With new discoveries and drugs and techniques birthing like bunnies, we wrote lots of papers and all of them required data. Copying numbers and text by hand from paper charts onto lined tablets was the only way we had of collecting information back then.

Before I left Pittsburgh, I worked with a colleague to build a clinical database It was primitive stuff, and we still had to enter all the information via a keyboard, but it streamlined the work we did with the statisticians.

In early 1992, nearly seven years after our move to Omaha, I began working with a couple of unemployed programmers to build an application they called OTTR (Organ Transplant Tracking Record) to follow liver transplant outpatients. By 2005, one of the original programmers and I had created a new application using a more modern coding language. By then, I was making rounds on inpatients with a tablet computer and creating billing-compliant inpatient notes on all of our patients. Each note was in the EMR ready for others to see by the time I walked out of patient rooms. Our presentation in 2008 asking for funding to expand our user group was approved in short order and by the end of November 2012, we had over 500 users of our software along with clear evidence of better billing and a marked reduction in the time required for documentation of clinical encounters, including operative notes. All three entities approved our budget proposal for three more years.

I was ecstatic.

Two months later, our program was cancelled. EPIC was coming.

I had assumed our program would keep my 14 colleagues and me happily making magic for at least another decade. Silly me.

Everyone on the team found great jobs within a couple of weeks. Their skills were in high demand. My bosses, however, wanted me to go back to the OR. I was 63 years old and hadn’t operated for over five years. I’d seen good surgeons’ skills start to fade years earlier than my age.

“No,” I said. “I’m not a surgeon anymore.”

I wasn’t sure what I would do, of course, but I had lots of ideas. Over the next several months I knocked on north of a dozen doors on campus proposing ways to make myself useful.

The path I followed next also originated in 2008. That year an Omaha poet, Steve Langan[ii], invited me to join a research project. As a subject. He had this crazy idea to pair seven doctors with seven professional writers and ask them to write stories or essays or poems together. Steve called it The Seven Doctors Project. Each week, one doctor-writer pair would read the two works they’d produced then sit back and bask in the praise from the rest of the group. I was assigned to a poet named Scott who taught creative writing at a local Catholic Women’s University. My piece was based on a novel I’d started the year before while at the Kenyon workshop. When our week came, Scott read first. He received warm praise. The group also applauded my piece, a mid-apocalyptic story of sorts. I was feeling pretty good about the responses and then Rebecca spoke.

“OK, the writing here is unquestionably that of someone with experience,” she said. “But lets’ go a little deeper.”

Rebecca pointed out all the ways in which my little piece failed to grab the reader and make them want to keep reading. “A reader roaming the aisles of Barnes and Noble who picks up a book that starts like this will have put it down, moved on after page two,” she said. As she continued, I began to see how terribly on target she was. She showed me what the piece needed and I wanted to get started immediately. I’d never had such direct and useful criticism of my writing before.

Steve had interviewed all of us before we started, exploring the states of our lives, our aspirations, our regrets, our hopes, and more. He interviewed us again at the end of the eight weeks. At a third interview one year later, he discovered that all seven doctors, as well as several of the writers had made major decisions about their lives that they all attributed to participation in the Project. One moved back to Virginia to start a practice in her hometown. Another quit his job in academia and joined a private practice. I started writing in earnest. I eventually convinced Rebecca to become my writing coach, and when Steve Langan decided to hold twice-yearly sessions of his Project, I participated in all of them. Most surprising to me, I began writing nonfiction and in the spring of 2010 I won first prize in a national writing contest with an essay titled “My Night With Ellen Hutchinson”[iii]. Within two years I had a literary agent who thought he could sell a book of my essays and in September 2015, that book was published by Penguin Random House[iv].

That book felt like both the hardest and most cherished success of my life. To become a surgeon, I simply followed a well-marked track. The steps were all laid out for me, and though a considerable amount of hard work was involved, the risk of failure was small. No such path exists for getting a book published and the risks of failure had always felt insurmountable. But finally, I was a writer. In a quiet moment after absorbing the news I heard my mom whisper: “What took you so long, Buddy?”

The most important benefit of writing and repeatedly editing the various essays that became the book wasn’t immediately apparent to me. Five years before the book came out, I slowly recognized that writing about the most emotionally laden experiences of my clinical career forced me to reprocess them in order to make the stories worth reading. I discovered the hard-wired versions of those experiences, the lens of resentment and anger, fear and despair through which I’d resolved them, draping them in a monochromatic cloak that allowed me to ignore the painful reality of each. Writing worthy narrative demanded I extract and accept the truth of experience and find a way to accept my role, and forgive myself, and others involved. I had to become far more self-aware, more compassionate.

The effect was powerful, and I found it hard to believe. If real, though, I figured someone else must have already studied it. That led me to the Internet and a robust body of research explaining what I had experienced. I became an avid student of reflective or emotional writing. I put together a slide show and began lecturing about what I’d learned. Eventually, I received approval to host several electives for senior medical students that provided them academic credit. I also started a Friday afternoon writing group called The Burnout Club. From two to as many as ten students would write for ten minutes in response to prompts I from me, then read and discuss their pieces. I chose prompts intended to elicit emotional responses and over the years discovered many very reliable ones. This will be the sixteenth year of hosting the Friday sessions.

I’ve also been participating in a variety of student courses involving M1 through M4 students. They include a surgical skills lab for third years, patient interview skills for first and second years, and several courses related to the economics, ethics, sociology, access and quality of healthcare. I host reflective writing sessions as are part of Psychiatry’s senior student stress management course.

I get the most enjoyment from hosting a literature and film elective for senior students. Each week for four weeks, we meet for two hours to discuss the week’s book and movie. I routinely pick books about which they will later say “I never would have read this had I not taken this course.”

I’m not sure when I’ll stop teaching. It has been my full-time job for more than a decade and I am still enjoying it. I hope to find some younger faculty (preferably surgeons) to become engaged in one or the other of my electives so that when I do quit the courses will continue.

I didn’t expect to be teaching medical students after leaving surgery. I had those other plans. I just knew I had to find something to do that felt important, that was rewarding. I understood the difficulty many surgeons had quitting. The OR is our refuge. It’s where we become the supreme commander. It’s where we face difficult challenges that demand manual skills, confidence-inducing experience, and good judgment. When it all comes together, when you work with a surgical tech who knows every step of your procedure and hands you the tools you need without you asking, and your assistants wield retractors and suction tips as though born to the craft, when the knife goes only where directed and bleeding responds to small blasts of cautery, when sponge and instrument counts are correct and the closure is perfect, it’s just plain magical. Why would anyone quit?

Dad did, and to my surprise, he took up woodworking. He built a shed on the side of his garage and after several years of Christmas, Father’s Day, and Birthday gifts, he had a very well outfitted shop. He bought stainless steel knife blanks and used found-wood that he carved into beautiful handles. At his peak output, he turned out dozens of full sets that included a filet knife, a cleaver, a boning knife, a paring knife, an 8” chef knife, and a serrated one that he called a sandwich knife but which looked like a Nancy Silverton knife. He claimed he sold enough of them to make ends meet, but I doubt that was true. He seemed more than happy to give sets away to friends or neighbors who might drop by. When he died at age 93, we found dozens of complete sets wrapped up in embroidered canvas sheaths that his wife made for him. We also found enough blocks of wood clogging his little shed to have kept him busy for another lifetime.

Dad also loved to fish. (Figure 4.) He remarried shortly after his retirement party, bought a double-wide on a canal in Palmetto, Florida. For 25 years, he and his wife spent Ohio’s four coldest months there and the other eight in Ohio. He made friends with locals who showed him their best fishing holes. The fishing dried up by the time Dad reached 89 years. Too much algae in the Bay, he said. With little else to do, he took to watching Bill O’Reilly from a recliner and sleeping away his afternoons. He thought climate change was a hoax.

Fortunately, his life during the eight months in Ohio remained much more active. He planted tomatoes and zucchini, made his knives, and later added Pens with wood barrels. He cut and hauled firewood, mowed his two acres, and water skied until his 85th summer. Every morning began with 10 laps of his backyard pool. For his 85th birthday we bought him an adult tricycle and he rode that thing up and down the neighborhood streets every day until the month before he died. His grandchildren, quickly became teenagers, then serious students, then parents who, before his death, bore him a bushel of great grandkids. He seemed happy. I think his Life After Surgery couldn’t have been more full.

My life after surgery hasn’t and won’t follow the path Dad’s took. I liked fishing with Dad, but not enough to spend time at it on my own time. I’ll never take up woodworking. My favorite activity with wood requires a chain saw and log splitter. We have a lot of deadfall from spring and summer storms. We burn a lot of firewood to keep warm in winter.

I think that making the most of life after quitting surgery requires more from us than life either before or during those years when the OR was our refuge. Not until I quit the OR did I discover how little experience I’d had with organizing my time. From soon after birth until our software project was cancelled, I spent most of my time showing up when and where someone else demanded. From waking to falling asleep, free time was a bonus and it felt great to do something other than what I was supposed to do. Even vacation dates, locations, and activities were often based less on my choices than on paying heed to external schedules.

Now it’s like waking up to a never-ending summer vacation. I know it won’t really last forever, but as long as I believe death is far off, making the most of free time feels more like something I ought to do than need or even want to do. Take tomorrow — a Saturday. I could mow. I’m way behind on that and the nettles are up to my chin already what with the rain and heat, but the tall grass is still wet from last night’s rain and with more forecast for tonight, mowing will be out.

I could clean out the garage. I’ve been putting that off all spring, but then there’s that threat of rain and if I start in the morning taking everything out onto the driveway sorting it, cleaning it then deciding what to do with it, the rain could ruin everything if it comes before I get stuff properly organized and back in the garage. I have too many things I should do that I apparently don’t have the will to tackle. It’s like not wanting to start a race for fear of losing.

Yes, I have always been a bit neurotic and as I write, I can hear my friend Dirk Noyes laughing. He has already decided what to do and we will not delay starting nor waste a moment of time today getting it done, and if it seems too easy, he’ll find a way to make it more challenging. He doesn’t share my obsession with deciding what’s right because whatever we do will be right as long as it tests us both a little bit.

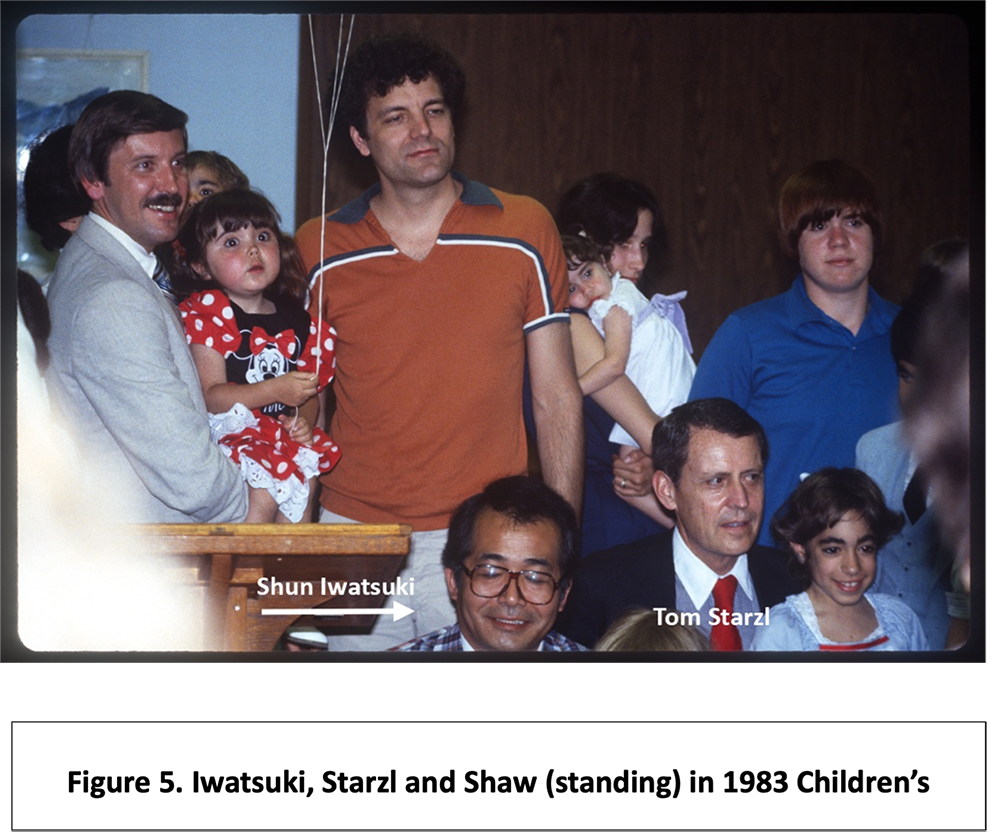

Three of my most important mentors died in the past five years: Shun Iwatsuki (Figure 5) and Frank Moody (Figure 6) in 2016, and Tom Starzl in 2017 (Figures 5 and 6.) Last week I lost another. Mike Sorrell, the hepatologist who was a key figure in the success of our liver transplant program, died with Parkinson’s Disease (Figure 7).

Along with Bing Rikkers, Mike was an invaluable source of support and joy for me when I moved to Nebraska. Mike was already a world-renowned figure in hepatology when he and Bing recruited me to start a transplant program in Omaha. His close relationship with other liver specialists around the US and abroad led to hundreds of patient referrals to our center during the first two decades.

My most indelible memories of Mike involve our expeditions to his old haunts in southeastern Nebraska in pursuit of wily Bobwhite quail. Mike invited me to hunt with him and his three sons during the first season of my tenure here. This was apparently unprecedented in the Sorrell family’s hunting tradition and caused no small apprehension among the scions. Even after many years of not having shot any of them, or their dogs, I was still carefully watched when out in the field with a gun.

I wish I’d spent more time with Mike after he retired. I don’t think he had nearly as much reward as when he was working full time. When I learned he was in poor health and deteriorating rapidly, I thought of Mitch Albom’s lovely memoir, Tuesday’s With Morrie.[v] I thought Mike and would have more time together before the end. I imagined weekly visits with him involving discussions of politics, books we’d read, and laughing about how many times he had to bring down a quail on-the-wing that I’d missed.

I saw him the evening before he died, but he was already unresponsive. I told him I loved him anyway. You never know.

For me, Life After Surgery is as much about the relationships we cultivate or destroy during our careers as it is about what we do with our time. I’ve touched on a handful of relationships in my life, and none have been more important than any others. All of the best ones include moments of stress, times when a stray word, or a moment’s insensitivity can either allow us to heal old wounds or split them open forever. I regret not having taken care of many connections and am joyous over the continuing durability of others. This week I’m missing a gathering of one of my dearest friends, his family and an assortment of other people I love but with whom I fear losing touch. They’re from the U.S., Australia, Sweden, Italy, and France. We once traveled together all over the world, flew to stay with them in their homes, hiked and biked and sailed with them. This past week I’ve become acutely aware of what could be at risk, and I still have so much I want to say and feel and do with so many people. The where and how isn’t important. It’s the when that needs choosing, and it needs to be sooner than later.

So Dirk, let’s pick a date as soon as you read this. Tomorrow won’t always be an option.

[i] https://kenyonreview.org/adult-writers/

[ii] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/steve-langan

[iii] https://creativenonfiction.org/product/issue-42/

[iv] https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/317669/last-night-in-the-or-by-byers-shaw/ and Figure 4

[v] Albom, M. (2017). Tuesdays With Morrie. Sphere.