Emergency Medicine

Engaging non-EMS transport to deliver Pre-Hospital Trauma Care in Peru

Since 2013, a group of health professionals from the University of Utah Department of Emergency Medicine and Primary Children’s Hospital have collaborated with local hospital and community leaders to decrease trauma morbidity and mortality in Cusco, Peru. Given the absence of a formal EMS system in the Sacred Valley, what could be done to harness the motivation of the community and maximize the potential of existing resources to provide effective pre-hospital care? The work that has emerged is to pilot basic trauma education to taxi drivers, the area’s default trauma transport mode, and to build a trauma registry that can guide decision-making, preventative education, and policy in the region.

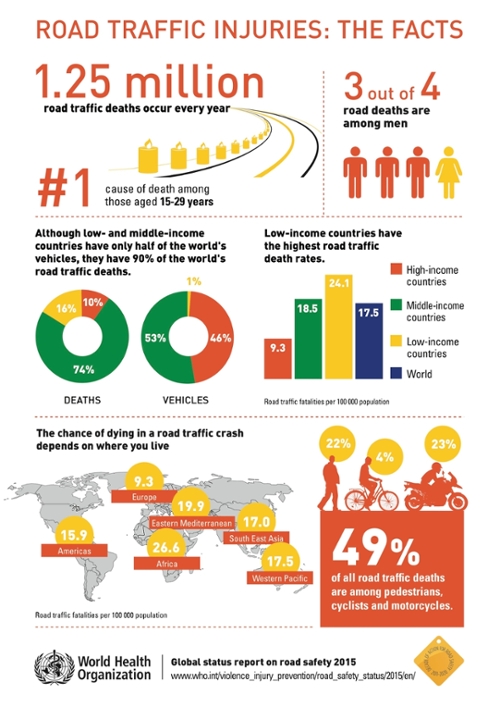

The lack of emergency medical services in Peru is just a drop in the bucket of an emerging global problem. The World Health Organization predicts that by 2030 road traffic injuries will be the fifth leading cause of death and the third leading cause of disease burden worldwide. While middle-income countries represent half of the world’s vehicles, they have 80% percent of the world’s road traffic deaths. The majority of these deaths occur pre-hospital, however many LMICs lack formal emergency medical services.

Research conducted early in the life of the project established that roughly 70 percent of trauma patients arrive to centers of care in Cusco, Peru via non-EMS methods. The team led by Dr. Matthew Fuller (EM Global Health Fellowship Director) including Dr. Matthew Stewart, Dr. Steve Hartsell(Division Chief), Dr. Jeff Robison (Pediatric Emergency Medicine) worked with local leaders to develop small group education flip books specially adapted to the largely illiterate population of local taxi drivers who are often the area’s first responders.

Of the 40 community members that participated in 2015’s two pilot courses, 60 percent had never taken a first-aid course. Pre- and post-course surveys demonstrated significant knowledge acquisition in the following first-responder techniques: basic airway opening maneuvers, placing patients in the rescue position, applying splints to fractured extremities, appropriate wound care, hemorrhage control, spinal immobilization, and patient transport. Following the course, participant comfort providing first-aid rose from 37 percent to 100 percent.

By engaging with real patient transportation trends in rural Peru, the current project has successfully developed and implemented a low cost trauma first-responder course to improve prehospital patient care. But determining just how this relates to total patient outcomes will require a formal trauma registry at large receiving hospital that would integrate patient information on mode of transport, treatment prior to arrival to the ED, with patient outcome data. Utah physicians are continuing to collaborate with Peruvian colleagues to establish a trauma registry at receiving hospitals and collect end-point patient data.

The achievements of this project will demonstrate that development of surrogate EMS systems and the creation of trauma registries has benefits for communities in low and middle income countries throughout the world. Future project goals include expanding training capacity, transitioning to in-country leadership, and correlating course implementation with an ultimate reduction in patient morbidity and mortality in the Cusco region of Peru.

Findings presented at:

- Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH)

- The Society of Academic Emergency Medicine

Click here for more information on the division of Emergency Medicine within the Department of Surgery. Infographic credit: WHO; photos credit: Crendos Allicance.